Our world is predominantly artificial, shaped by human design. This realization has profound implications for us as individuals and designers. It empowers us to challenge and reimagine the systems, processes, and artifacts that make up our lives, including education. By acknowledging the artificiality of our world, we gain agency to envision and create a more equitable and effective educational system.

Recognizing that we live, for the most part, in an artificial, human-created world can change how we are in the world, how we perceive it, interact with it, and, more importantly, how we can change it. One could argue that it also provides us with a moral imperative to do so because we know that much of the world around us is unfair, often disadvantaging and marginalizing huge swaths of people and communities. Since there is nothing inherently “natural” about these artifacts or processes or systems, we have the agency to change them.

Included in this artificial world is education. Almost every aspect of what makes up today’s educational system—classes, schools, credit hours, universities, degrees, even the very idea of receiving an “education”—has been invented by humans. The current design of education does not work for many, particularly the groups that have been historically marginalized. If schools are not fun, if they do not support play and creativity, it is because they are designed to be this way (either intentionally or by happenstance as a side effect of some other decisions that were, at that time, believed to me more important). Because these are creations of humans, they can be reimagined and redesigned for better outcomes. Although the changing educational system might be incredibly complex, it is worth recognizing that it is designed and so can be re-designed.

In our work, we have found that expanding what we see as artificial, particularly the artificial nature of education and schooling, can enable powerful change. It is enabling in two ways. First, it allows us to interrogate everything around us, not taking it as a given, but rather something that was created and thus can be re-created, re-imagined, and re-designed. Second, it provides a response to those who resist change by making an essentialist argument — “this is just how things are.” Acknowledging the artificiality of the system suggests that this is how things may be, but they don’t have to be this way.

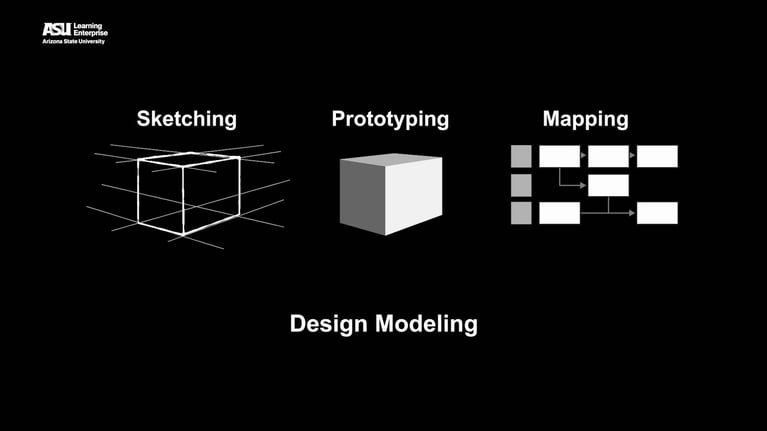

Another important aspect of seeing the world as artificial is expanding what we mean by the “world.” For too long we (and the field of design) have conceived of the designed world as constituted of physical artifacts and other technological tools. Although these are important, we argue that there are many intangible aspects to the designed world. They may include experiences (such as the feeling of awe when faced with the immensities of the cosmos); processes (such as the process of registering for school), systems (such as the K-20 educational system), or even culture (such as the culture of high-school football). Although design in some spheres (such as systems and culture) might be more complex than others, applying a wide-angled design lens can increase agency, empowering change makers. In order to do so, we need a frame, a way of categorizing or classifying the different kinds of “designed things” that are out there in the world.

We have created a framework that supports applying this type of design lens to education. The Five Spaces for Design in Education framework presents design as occurring across five interactive spaces: artifacts, processes, experiences, systems, and culture . The framework provides an analytical tool for understanding the relationships among designed entities, shifting perspectives, and offering new possibilities for re-design.

What is common across these spaces is the idea of intentional design and the manner in which designers (whether they be designing an educational app or the culture of a school) approach the work, how they think and act.